Whiskey is a captivating liquor.

When first poured into a wooden cask, its components are eminently simple – water and a mash of grains. But by the time it’s poured into a glass, years or perhaps decades later, it may be the very pinnacle of complexity.

Whiskey conjures sharply conflicting images. It is a dark brown liquid in a dusty bottle in a dirty saloon in the old West. It is a supporting player in a sugary cocktail. It is a status symbol at $70 a glass in an elegant lounge.

In that respect, it is an everyman’s drink. At the same time, whiskey is very much an acquired taste. The heavenly quality of even the oldest, smoothest single malt would be wasted on the palate of the uninitiated.

I remember my first sip of whiskey, if you can even call it a sip; I don’t honestly recall whether it made it past my lips. As I lifted the glass, I felt a strange presence tickling my nose hairs, and my upper lip twisted upward into an involuntary snarl. How does anyone drink this, I wondered.

Because yes, your first sip of whiskey burns. As does your second. And your third.

But what begins as repulsion grows to a challenge – can you drink it without cringing? It then becomes a badge of honor when you can order a glass of whiskey on the rocks and down the whole thing by yourself. Gradually, despite your earlier misgivings, you develop an appreciation. And by the time someone pours you a rich, velvety, 21-year-old single malt whiskey, you’ve fallen deeply, hopelessly in love.

But what begins as repulsion grows to a challenge – can you drink it without cringing? It then becomes a badge of honor when you can order a glass of whiskey on the rocks and down the whole thing by yourself. Gradually, despite your earlier misgivings, you develop an appreciation. And by the time someone pours you a rich, velvety, 21-year-old single malt whiskey, you’ve fallen deeply, hopelessly in love.

That potent liquid no longer gives you the shivers, but it’s a full-body experience just the same. Your lips tingle as you take the first sip. And you don’t just quaff it down; you sit with it. Its oaky, smoky essence permeates every corner of your mouth, and a small flame burns in the back of your throat when you finally swallow it. After a few sips, a warmth unique to whiskey slowly spreads, up from your belly, across your limbs, and down through your extremities.

A fierce, centuries-long debate continues to rage between the Irish and the Scots as to who is responsible for first distilling this mysterious spirit. As my bloodlines trace to both Ireland and Scotland, I don’t have too much of an opinion on the matter, but I admit more evidence points to the Emerald Isle. If Ireland can claim victory in the argument over who invented whiskey, though, Scotland is the undisputed champion of modern-day distribution. Ninety million cases of Scottish whisky get shipped to all corners of the globe every year, while Ireland ships a relatively modest 5 million cases.

The seeds of that disparity were planted in the late 19th century, when the Scottish embraced cheaper, more efficient methods for distilling whisky while the Irish insisted on a more traditional approach that took more time but yielded more flavor. Quicker production meant a bigger market share for the Scots, and that was even before a series of calamities struck the Irish whiskey industry. First, Ireland’s War of Independence ravaged its export business during 1919–1921. Emerging from that struggle, Irish distillers discovered they had lost their biggest customer, the United States, on account of Prohibition. And worse, bootleg knockoffs of Irish whiskey that proliferated in the States during that period tainted the spirit’s reputation. The U.S. markets reopened in 1933, but by then the world was on the cusp of war, and the effects of World War II nearly destroyed the Irish whiskey industry entirely. Most of the remaining Irish distilleries soon closed or merged, and while the quality of Irish whiskey never diminished, its level of output never recovered.

But an interesting thing happened last year – in 2011, for the first time in decades, Irish whiskey outsold single malt Scotch in the United States. And that’s part of a global trend. While Scottish whisky still captures 60% of the market, sales of Irish whiskey are noticeably on the rise.

I asked Tim Herlihy, U.S. brand ambassador for Ireland’s Tullamore D.E.W. whiskey, why that was, and he attributed the renaissance of Irish whiskey to its accessibility. “There are so many rules about Scotch,” he said. “With Irish whiskey, you can drink it neat, on the rocks, with water, in ginger ale, as a shot; it’s easy.”

Tullamore D.E.W. hosted a whiskey tasting at the Asgard in Central Square this week, and Tim invited me to have a drink with him beforehand to talk shop. Free whiskey and a chance to chat with someone who drinks for a living seemed like the foundation for a pretty decent evening, so I was happy to oblige.

If you’re unfamiliar with Tullamore D.E.W., it’s no surprise. Although Tullamore D.E.W. is the second most popular brand of Irish whiskey in the world, it’s a distant third in the United States, behind Jameson, the almighty industry leader, and Bushmills. But sales of Tullamore D.E.W. have nearly doubled since 2005 on the heels of an aggressive marketing campaign that promotes Tullamore D.E.W.’s long history and tradition. A redesigned label reminds drinkers that Tullamore D.E.W. has been distilling continuously since 1829. Even the name has gotten a subtle makeover: what was once Tullamore Dew is now Tullamore D.E.W. The initials are those of one of the distillery’s earliest owners, Daniel E. Williams, whose struggles to bring his product to prominence in the 19th century are reflected in Tullamore D.E.W.’s present efforts to compete in a crowded global market.

Tim told a few good stories about life in Ireland and his international travels, offered up some traditional Irish toasts, and most importantly, treated me to samples of Tullamore D.E.W.’s four whiskey varieties. First up was Tullamore’s original whiskey – a rich, amber color, spicy and citrusy up front, with a smooth finish.

Tim told a few good stories about life in Ireland and his international travels, offered up some traditional Irish toasts, and most importantly, treated me to samples of Tullamore D.E.W.’s four whiskey varieties. First up was Tullamore’s original whiskey – a rich, amber color, spicy and citrusy up front, with a smooth finish.

My first experience with this particular variety was at the Buena Vista Café in San Francisco – the very bar that introduced the wonder of Irish coffee to the United States. The Buena Vista (“a great Irish bar,” Tim said, reverently) makes its famous drink exclusively with Tullamore D.E.W., which means tens of thousands of customers have tried Tullamore whether they know it or not.

My first experience with this particular variety was at the Buena Vista Café in San Francisco – the very bar that introduced the wonder of Irish coffee to the United States. The Buena Vista (“a great Irish bar,” Tim said, reverently) makes its famous drink exclusively with Tullamore D.E.W., which means tens of thousands of customers have tried Tullamore whether they know it or not.

The original blend is easy to drink, just as Tim suggested. But an established Scotch drinker doesn’t require a gentle, accessible whiskey. So what about those of us who enjoy the ceremony and pretension of drinking a more complex spirit? “Well,” Tim said, smiling, “that’s why we have this.” He then unveiled Tullamore D.E.W.’s 10-year-old single malt whiskey. Matured in four casks – bourbon, sherry, port, and Madeira – the single malt was considerably more intense than the original. With a rich, floral aroma, notes of vanilla and toasted wood, and a smooth finish, the single malt would appeal to those who prefer the complexity of a finer whiskey. If you live locally, you’ll just have to take my word for it; sadly, the 10-year single malt is not yet available in Massachusetts.

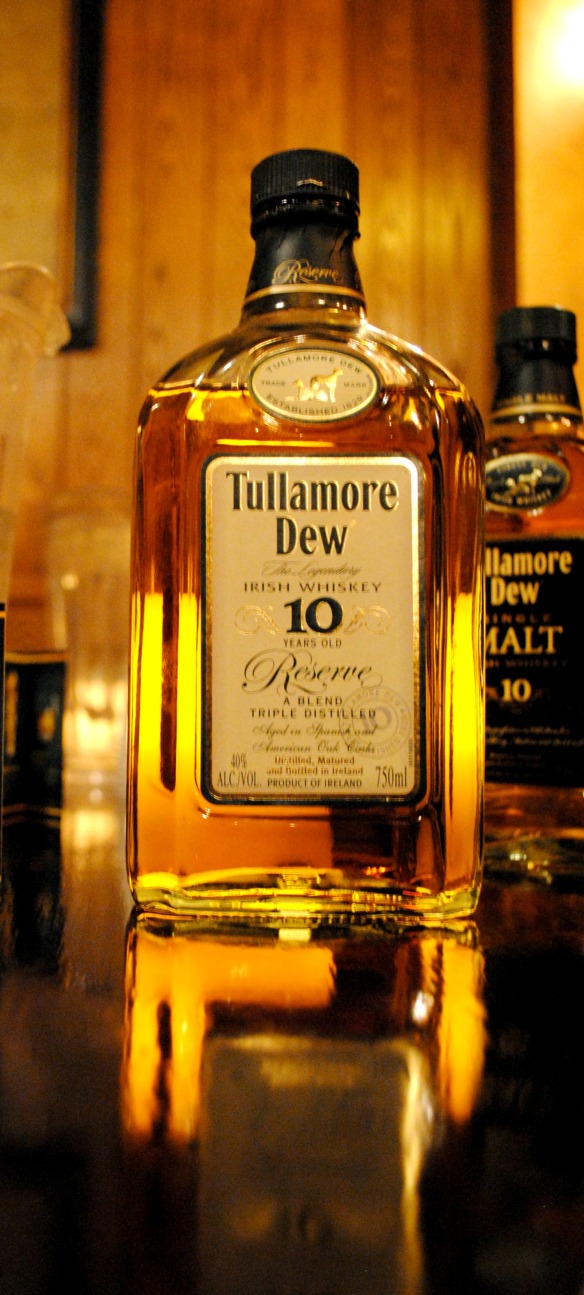

Next up was a 10-year-old reserve, a soft, medium-bodied whiskey with a spicy finish. This one was altogether different. Luxuriously smooth, the 10-year reserve possessed a sweetness that its predecessors lacked, along with a distinctive, surprising creaminess. It was probably my favorite of the four, and I know I’m not the only one who was impressed – the 10-year reserve won Best in Show at the 2012 Los Angeles International Spirits Competition, 2012. Sláinte!

Next up was a 10-year-old reserve, a soft, medium-bodied whiskey with a spicy finish. This one was altogether different. Luxuriously smooth, the 10-year reserve possessed a sweetness that its predecessors lacked, along with a distinctive, surprising creaminess. It was probably my favorite of the four, and I know I’m not the only one who was impressed – the 10-year reserve won Best in Show at the 2012 Los Angeles International Spirits Competition, 2012. Sláinte!

The final sample was a real treat – a 12-year-old special reserve. Full-bodied, spicy, and pleasantly intense, the 12-year is matured in sherry casks and had a nutty flavor with hints of vanilla. It’s garnered several international awards, most recently serving as runner-up to the 10-year reserve in the same spirits competition earlier this year.

The final sample was a real treat – a 12-year-old special reserve. Full-bodied, spicy, and pleasantly intense, the 12-year is matured in sherry casks and had a nutty flavor with hints of vanilla. It’s garnered several international awards, most recently serving as runner-up to the 10-year reserve in the same spirits competition earlier this year.

As Tullamore D.E.W. rides the wave of Irish whiskey’s global resurgence, things are going well in the homeland, too. Production of Tullamore D.E.W. is about to return to the town of Tullamore for the first time since the original distillery closed in 1954. Owner William Grant & Sons is investing €35 million in a state-of-the-art distillery that is scheduled to break ground next month, creating jobs in Tullamore and restoring a sense of civic pride to a town that has had to endure its namesake whiskey being distilled elsewhere for almost 60 years.

As Tullamore D.E.W. rides the wave of Irish whiskey’s global resurgence, things are going well in the homeland, too. Production of Tullamore D.E.W. is about to return to the town of Tullamore for the first time since the original distillery closed in 1954. Owner William Grant & Sons is investing €35 million in a state-of-the-art distillery that is scheduled to break ground next month, creating jobs in Tullamore and restoring a sense of civic pride to a town that has had to endure its namesake whiskey being distilled elsewhere for almost 60 years.

Four satisfying samples later, I found myself more informed about Irish whiskey and Tullamore D.E.W. in particular. I didn’t even know they had more than one variety, and experiencing the whole range was enlightening. Tim closed our evening with a toast – “Here’s to cheating, stealing, fighting, and drinking. If you cheat, may you cheat death. If you steal, may you steal a heart. If you fight, may you fight for a brother. And if you drink, may you drink with me.”

Any time, good sir.

Last Call: Everything about whiskey requires patience. The liquor itself takes years to mature. When it reaches your glass, you sip it slowly. And a lifetime of enjoying it is equal parts education and appreciation. It takes time to understand the nuances of single malts vs. blends, or the distinct qualities of Scotch, Irish whiskey, bourbon, and rye. Only a fair amount of trial and error will reveal which brands work well in a Manhattan, which types are enhanced by a cube of ice, and which varieties absolutely, positively must be consumed neat. Your personal preference, like the character of a good whiskey itself, needs time to fully emerge.

Last Call: Everything about whiskey requires patience. The liquor itself takes years to mature. When it reaches your glass, you sip it slowly. And a lifetime of enjoying it is equal parts education and appreciation. It takes time to understand the nuances of single malts vs. blends, or the distinct qualities of Scotch, Irish whiskey, bourbon, and rye. Only a fair amount of trial and error will reveal which brands work well in a Manhattan, which types are enhanced by a cube of ice, and which varieties absolutely, positively must be consumed neat. Your personal preference, like the character of a good whiskey itself, needs time to fully emerge.

If you’re a novice, attending a whiskey tasting can provide for an illuminating introduction to this potent spirit. But even if you’re an established whiskey enthusiast, there’s always something new to learn, or to impart to others. That said, I’m grateful to Tim for inviting me out for a few drinks. Truly, one of the most fulfilling things about appreciating whiskey is having a conversation with someone who understands and shares your passion. After all, learning to enjoy whiskey can be a long journey, and it’s always a pleasure to meet a fellow traveler.